Have you ever opened your mutual fund statement, seen that its value has barely budged, yet still gotten hit with a surprise tax bill? It’s a frustratingly common scenario for investors, and it’s all thanks to something called a capital gains distribution. Even if your fund’s share price goes nowhere, you can end up owing taxes because of what the fund manager is doing behind the scenes.

The Phantom Tax Bill From Your Mutual Fund

It helps to think of a mutual fund not as one single investment, but as a big container holding dozens or even hundreds of different stocks and bonds. The fund's share price, known as its Net Asset Value (NAV), is simply the total market value of everything inside that container. But that single number doesn't reveal the whole picture.

Throughout the year, your fund manager is actively trading—buying new assets and selling existing ones. When they sell a stock or bond for more than they paid for it, that creates a "realized" capital gain. U.S. law requires mutual funds to pass these realized gains on to their shareholders, which they typically do once a year. That payout is the capital gains distribution.

The Disconnect Between Performance and Taxes

This is where the wires get crossed for so many investors. You’re being taxed on the fund’s internal selling activity, not its overall performance for the year. A fund’s NAV could be flat or even down, but if the manager sold off a few big winners that they’d held for years, you could still get handed a hefty distribution—and the tax bill that comes with it.

Key Insight: A capital gains distribution isn't new money in your pocket. It's a return of capital that was already factored into the fund's value. When the distribution is paid, the fund's NAV drops by the exact same amount, because that cash is no longer in the fund—it’s been paid out to you.

This is exactly why investors can get taxed even in a terrible market. We saw significant capital gains distributions from mutual funds during the 2008 financial crisis and again in down years like 2018 and 2022, just as investors were watching their portfolio values shrink. You can read the full research on how distributions persist in all kinds of market conditions.

To make this clearer, let's look at a few different market scenarios. This table shows how a fund's overall performance doesn't neatly predict whether you'll get a distribution.

Fund Performance vs. Capital Gains Distributions

| Scenario | Fund's Net Asset Value (NAV) Change | Potential for Capital Gains Distribution | Reason for Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bull Market | Fund NAV increases 15% | High | The manager sells winning stocks to lock in profits or rebalance the portfolio. |

| Flat Market | Fund NAV is unchanged | Moderate to High | The manager sells older, highly appreciated stocks to buy new ones or to raise cash for departing shareholders. |

| Bear Market | Fund NAV decreases 10% | Moderate | The manager is forced to sell appreciated stocks to cover a wave of investor redemptions (withdrawals). |

As you can see, distributions can happen anytime. Even in a down market, if lots of investors are selling their shares, the manager might have to sell the fund’s long-held winners to generate the cash needed to pay them out.

Ultimately, this "phantom tax" is just a baked-in feature of the mutual fund structure. The manager's decisions to sell assets inside the fund directly create a tax liability for you, the shareholder, regardless of whether you personally sold a single share. Understanding this hidden cost is absolutely critical for smart tax planning.

Decoding Why Your Fund Issues a Payout

Capital gains distributions don't just happen out of the blue. They’re a direct result of a fund manager's day-to-day work—making smart moves within the portfolio. If you can get a handle on what triggers these payouts, you can stop being surprised by them and start anticipating them.

Think of a fund manager like a head chef running a busy kitchen. That chef is constantly swapping out older ingredients for fresh ones to keep the dishes top-notch. In the same way, a fund manager sells securities for all sorts of strategic reasons, and each sale can trigger a taxable event that lands in your lap.

Locking in Profits and Rebalancing the Portfolio

The most common reason for a distribution is simple profit-taking. Let's say your fund manager bought a stock for $50, and it has since shot up to $150. They might decide to sell that position to lock in the gain. That $100 profit per share is a "realized" capital gain, and by law, the fund has to pass it along to its shareholders.

This often happens when it's time to rebalance the portfolio. An actively managed fund might have a rule that no single stock can make up more than 5% of its assets. If a hot stock rockets up and becomes 8% of the fund, the manager has to sell some of it to get back to the target weight. It's a disciplined, smart move, but it also generates taxable gains for you.

Getting a Grip on the Fund's Cost Basis

To really get this, you have to understand the idea of a fund's cost basis. This isn't what you paid for your shares. It's the original price the fund paid for its assets, which could have been years or even decades ago.

Imagine your fund snapped up shares of "XYZ Corp" ten years ago for $20 a pop. Today, those same shares are trading at $200. The fund's cost basis is still that original $20. If the manager sells them now, the fund realizes a huge $180 per-share gain, which gets distributed to investors.

Crucial Takeaway: You inherit the tax liability of all the gains a fund has built up over its entire history, even if you just invested yesterday. Buying into a fund with big, long-held winners means you're also buying into its future tax bill.

Dealing with Shareholder Redemptions

Another major trigger for distributions is something you have absolutely no control over: other investors. When a bunch of shareholders decide to cash out (a process called redemption), the fund manager has to come up with cash to pay them.

Where does that cash come from? The manager has to sell assets from the portfolio. And what do they usually sell first? Often, it's the most appreciated, long-held stocks because they're the easiest and quickest to liquidate. This selling action crystallizes gains for the fund, which are then passed on to the remaining shareholders—that includes you.

Why December Is Distribution Season

While payouts can technically happen anytime, there's a definite seasonal rhythm to them. Most funds wrap up their fiscal year on October 31 for calculating capital gains. They are required to distribute at least 98.2% of their net capital gains from that period to avoid paying a nasty 4% excise tax themselves. This rule creates a flurry of activity at the end of the calendar year.

And the scale of these payouts is massive. One study found that U.S. mutual funds distributed a jaw-dropping $234 billion in long-term capital gains in a single year. About 38.3% of those distributions happened in December alone. You can discover more about the timing of fund distributions and their market impact.

This is why you’ll see fund companies post their estimated capital gains distributions in November. They're giving you a heads-up before the payouts hit in December. Once you understand this cycle, a potential tax surprise becomes just another expected part of the investment calendar.

Calculating the Real Cost of Your Distribution

Understanding why distributions happen is one thing, but figuring out their real cost is where the rubber meets the road. This is the moment a theoretical concept like capital gains distributions in mutual funds becomes a real tax bill you have to deal with. For any serious investor, it’s a critical piece of the puzzle.

What surprises many investors is that distributions are taxable the year you get them, even if you never actually see the cash. Most of us automatically reinvest distributions to buy more shares of the fund. While that’s fantastic for compounding your growth over time, it doesn’t get you out of paying taxes. The IRS treats that reinvested money as income you received and then chose to put back into the fund, making it a taxable event.

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Gains

The tax rate you'll pay on that distribution isn't based on how long you’ve held the fund. Instead, it all comes down to how long the fund owned the stocks or bonds it sold. This is a crucial distinction that creates two different kinds of taxable gains.

- Long-Term Capital Gains: These come from the fund selling assets it held for more than one year. They get taxed at more favorable rates (0%, 15%, or 20%), which are usually much lower than your standard income tax rate.

- Short-Term Capital Gains: These happen when the fund sells assets it held for one year or less. The IRS taxes these gains just like regular income, which can mean a much higher tax bill.

Your fund company will send you a Form 1099-DIV early in the new year breaking down exactly how much of your distribution was long-term versus short-term. Paying close attention to this form is essential for filing your taxes correctly. A fund with a high turnover ratio often racks up more short-term gains, leading to a bigger tax headache. This is one of many metrics analysts look at; you can learn more about how to understand stock analyst ratings to see how these details fit into the bigger picture.

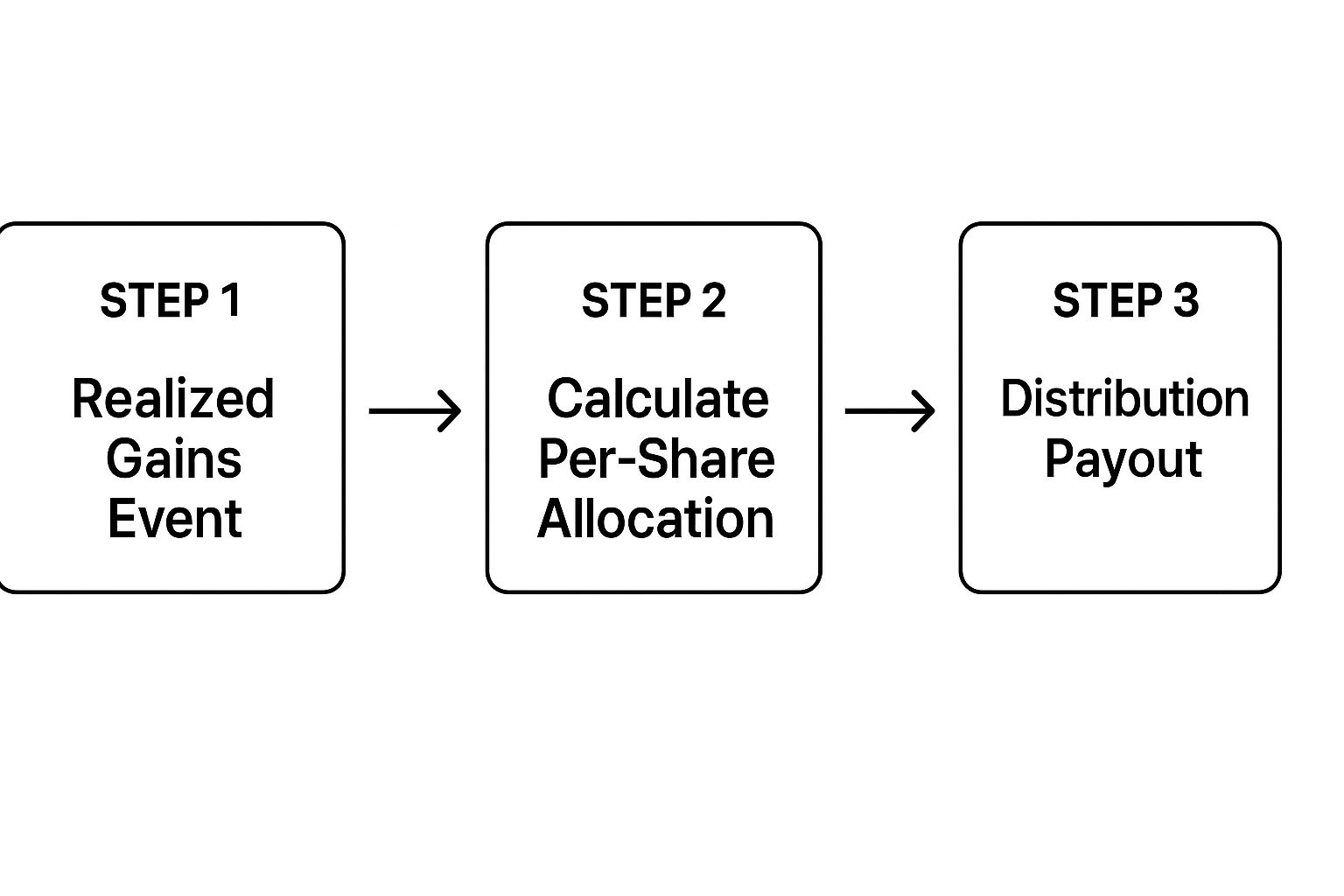

This graphic shows how a fund's internal profits are calculated and eventually passed on to you.

As you can see, it's a pretty straightforward journey from the fund manager taking profits to a taxable payout for you, the shareholder.

As you can see, it's a pretty straightforward journey from the fund manager taking profits to a taxable payout for you, the shareholder.

A Practical Tax Calculation Example

Let's walk through a quick scenario to make this crystal clear.

Imagine you put $10,000 into the "Growth Fund" at $25 per share, which gets you 400 shares. At the end of the year, the fund announces a long-term capital gains distribution of $2.00 per share.

Calculate Your Total Distribution:

- 400 shares x $2.00/share = $800

- This $800 is your taxable distribution for the year.

Calculate Your Tax Bill:

- Let's say you're in the 15% long-term capital gains tax bracket.

- $800 x 0.15 = $120

- You owe the IRS $120, even if you reinvested the entire $800.

See the Impact on Your Fund's Value:

- On the ex-dividend date, the fund's share price (NAV) will drop by the distribution amount, from $25 to $23.

- Your original shares are now worth: 400 shares x $23/share = $9,200.

- That $800 distribution is used to buy new shares at the lower $23 price, giving you an extra 34.783 shares.

After it's all said and done, you now own 434.783 shares worth a total of $10,000. Your overall investment value is the same, but you have a $120 tax bill to show for it.

The Reinvestment Trap: Forgetting to adjust your cost basis is one of the most common and expensive mistakes an investor can make. Your original cost basis was $10,000. After reinvesting the $800 distribution, your new adjusted cost basis is $10,800.

If you forget to track this and later sell your shares, you might only report the original $10,000 cost basis. This slip-up would cause you to overstate your gains and pay taxes on that $800 distribution a second time. Diligent record-keeping is your best defense against this double-taxation pitfall.

How Market Trends Fuel Taxable Payouts

Those capital gains distributions from mutual funds don't just appear out of thin air. They're a direct result of the market's mood swings, and figuring out how booms and busts affect these payouts is the key to guessing the size of your next tax bill.

Think of a long bull market as a pressure cooker for your mutual fund. As stock prices climb year after year, the fund quietly builds up massive unrealized gains on stocks it's held for a long time. These are often called embedded gains—a giant, lurking tax liability just waiting for the manager to hit the "sell" button.

The Bull Market Effect

The tech boom of the late 1990s is a classic example. As tech stocks went to the moon, funds holding them saw their internal profits swell to insane levels. When managers finally decided to sell those high-flyers to lock in gains or rebalance their portfolios, they unleashed a firehose of capital gains distributions on their shareholders for years to come.

You can see this play out in the data. Between 1990 and 1997, as the bull market roared, annual capital gains distributions from U.S. mutual funds exploded from $8 billion to a staggering $183 billion. This wasn't a coincidence; it was a direct consequence of rising stock prices. When the market cooled off in 1998, distributions predictably dipped to $165 billion. If you're curious, you can dig into the full CBO report on this trend and see the connection for yourself.

A Critical Connection: A long bull run almost guarantees that funds will be sitting on huge embedded gains. Even if you buy into the fund near the market's peak, you're essentially inheriting the tax bill for profits that were built up years before you even showed up.

This buildup of pressure means the tax pain can stick around long after the party's over. Fund managers might keep selling those appreciated stocks for years, triggering big distributions even after the market has gone sideways or down.

The Bear Market Paradox

You'd think a bear market would mean fewer distributions, right? Not so fast. That's a dangerous assumption, because a market downturn creates a totally different kind of pressure that can be just as good at triggering taxable events.

When the market tumbles, panicky investors often sprint for the exits, demanding their money back. This wave of investor redemptions forces the fund manager to sell assets to raise cash and pay out those departing shareholders.

So, what do they sell to get the cash?

- They can't sell the losing stocks—that won't raise enough money and just locks in a loss.

- Instead, they're often forced to sell the fund's long-held winners, the very stocks with the biggest embedded gains.

This creates a painful paradox. The investors who are fleeing the fund actually force the manager to sell winning stocks, which triggers capital gains for the loyal, stay-the-course shareholders left behind. It’s a gut-punch scenario: you could be watching your fund’s value drop while getting hit with a tax bill for gains you never even enjoyed.

This is where understanding investor psychology becomes so important. Learning how to use market sentiment analysis for trading can give you a real edge, helping you see how widespread fear and greed can drive these exact kinds of market movements.

Actionable Strategies to Minimize the Tax Bite

Knowing why capital gains distributions in mutual funds happen is one thing. Actually doing something to soften the tax blow is what really protects your returns over the long haul.

Once you understand the mechanics, you can stop being a passive bystander to your tax bills and start actively managing your financial outcome. This isn't about shady tax evasion—it's about smart, legal moves to make your portfolio more efficient. Let’s walk through a few practical ways you can sidestep, delay, or shrink the taxes from these yearly payouts.

Time Your Purchases Carefully

One of the simplest yet most overlooked tactics is all about timing. As the end of the year rolls around, mutual fund companies start releasing their estimated distribution schedules. This is your signal to pay attention, especially if you’re about to invest a fresh lump sum.

Fund companies will announce three crucial dates:

- Record Date: The final cutoff. If you own shares by the end of this day, you get the distribution (and the tax bill).

- Ex-Dividend Date: The day the fund starts trading without the value of the distribution priced in. If you buy on or after this date, you miss the payout—and the tax hit.

- Payable Date: The day the distribution actually lands in your account, either as cash or as new shares.

Buying a mutual fund right before the record date is a classic rookie mistake. You're essentially paying for a tax liability you didn't need to take on, since you'll owe taxes on gains you didn't even hold the shares for. The much smarter move? Just wait until after the ex-dividend date to buy. You’ll completely sidestep that immediate tax bill.

Use Tax-Advantaged Accounts Wisely

This might be the most powerful strategy in the entire playbook: asset location. It’s the simple idea of putting the right investments in the right accounts to maximize what you keep after taxes.

Tax-advantaged accounts like a 401(k) or a traditional IRA are the perfect home for your most tax-inefficient funds. Inside these accounts, capital gains distributions happen behind a tax-proof shield. You won't see a tax bill for them year after year. All the taxes are deferred until you start pulling money out in retirement, letting your investments compound without that annual tax drag.

Key Strategy: Stash your mutual funds with high turnover or a history of big distributions inside your IRA or 401(k). This protects those payouts from annual taxes and lets your money grow without interference.

On the other hand, more tax-friendly investments like index funds or most ETFs are a better fit for a regular, taxable brokerage account.

Consider Tax-Efficient Alternatives

If you're investing in a taxable account, it pays to look for funds built from the ground up to minimize taxes.

- Tax-Managed Funds: These are mutual funds where the manager's primary job is to boost your after-tax return. They actively try to avoid triggering taxable events by offsetting gains with losses (a process called tax-loss harvesting) or holding winners long enough to qualify for lower long-term capital gains rates.

- Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): While not totally immune, most ETFs are structured to be far more tax-efficient than mutual funds. Because of the way shares are created and redeemed, ETFs can often get rid of appreciated stocks without selling them and realizing a taxable gain. This results in fewer and smaller distributions for you.

Switching to one of these can make a huge difference in a taxable account. But remember, tax efficiency is just one piece of the puzzle. You still need to make sure the fund's strategy and fees fit your goals. High fees can be a silent portfolio killer. To get a better handle on this, you can understand asset management fees and save more on investments with our detailed guide.

Ultimately, dealing with the tax hit from capital gains distributions in mutual funds is all about being proactive. By timing your buys, using the right accounts, and choosing tax-smart products, you can keep more of your hard-earned money working for you.

Your Questions on Capital Gains Distributions Answered

We’ve walked through the mechanics, tax hits, and strategies for dealing with capital gains distributions in mutual funds. Still, I find that once investors start applying these ideas to their own portfolios, specific questions always pop up.

This section is all about tackling those common queries head-on. Think of it as your go-to playbook for the real world. We'll get into what happens if you sell your shares right after a payout, which tax forms to watch for, and how to read the tea leaves on a fund's distribution size. Let’s get into the details that truly matter.

What Happens if I Sell My Shares Immediately After a Distribution?

This is a classic point of confusion, and for good reason. When a fund makes a distribution, its share price (the Net Asset Value or NAV) drops by the exact amount of that payout. So, if your fund is trading at $50 per share and hands out a $2 distribution, its NAV will immediately fall to $48.

If you sell right after that drop, it looks like you've taken a capital loss on paper. Your shares are now worth less than they were yesterday. But here's the catch: you can't use that "loss" to cancel out the taxable gain from the distribution you just got.

Why not? The IRS sees them as two separate events. You still have to report the $2 per share distribution as taxable income for the year. The loss you created by selling can only be used to offset other capital gains you might have, or a small portion of your regular income.

Which Tax Forms Should I Look For?

Keep a close eye on your mail—or inbox—in January and February. Your mutual fund company is legally required to send you a summary of all the distributions you received during the previous year.

The single most important document is Form 1099-DIV, Dividends and Distributions. This form neatly breaks everything down for the IRS, telling you exactly what you need to report.

- Box 1a shows your total ordinary dividends.

- Box 2a shows your total capital gain distributions, which are mostly long-term gains.

This form is your roadmap for filing your taxes correctly. Ignoring it is a recipe for penalties and a headache you don't need.

Is a Large Distribution a Good or Bad Sign?

This is a great question because the answer is, "it depends." A massive distribution isn't automatically a good or bad thing; it’s a signal that tells you to dig a little deeper. The context is everything.

A large distribution might mean:

- Good News: The fund manager had a fantastic year, skillfully navigating the market and locking in big profits from winning stocks. It’s a sign of success.

- Bad News: The fund was hit with a wave of investor withdrawals (redemptions), forcing the manager to sell stocks to raise cash. This often happens in a down market and can be a sign of instability.

- Neutral News: A new manager took over and is "cleaning house"—selling off the previous manager's picks to realign the portfolio with their own strategy.

Key Takeaway: Never judge a distribution in a vacuum. Look at the fund's turnover ratio, its recent performance, and any news about manager changes. A huge payout from an underperforming fund with high turnover is a major red flag. A payout from a top-performing fund is often just the price of winning.

Why Do ETFs Have Fewer Capital Gains Distributions?

While they look similar on the surface, mutual funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) are built differently under the hood. This structural difference is what makes ETFs so much more tax-efficient. It all comes down to how they handle investor buy and sell orders.

When you sell your mutual fund shares, the fund manager often has to sell some of its underlying stocks to give you your cash back. That sale is what triggers the taxable capital gain.

ETFs, on the other hand, have a clever workaround called an "in-kind" redemption process. When large institutional investors want to cash out, the ETF doesn't sell stocks. Instead, it simply hands them a basket of the actual stocks from its portfolio. Because no sale occurs, no taxable event is triggered. This is why ETFs pass on far fewer, if any, capital gains distributions to mutual funds investors.

Should I Sell a Fund to Avoid a Big Distribution?

This is a classic "six of one, half a dozen of the other" dilemma. Selling a fund just to sidestep a distribution might feel smart, but remember, the sale itself is also a taxable event. You have to run the numbers.

Here’s a simple way to think about it:

- Estimate the Tax on the Distribution: Your fund will announce its estimated per-share distribution. Multiply that by your number of shares to see the total taxable amount coming your way.

- Calculate the Tax on the Sale: Next, figure out the capital gain you'd realize by selling your shares today. Then calculate the tax you'd owe on that gain.

If the tax bill from selling is lower than the tax bill from the distribution, a sale might make sense. This is often the case if you're sitting on a capital loss or a tiny gain. But if selling would lock in a large gain of your own, you're almost always better off just holding on and accepting the distribution. It's a math problem, pure and simple.

Understanding the nuances of market sentiment can provide an edge in anticipating market trends that fuel fund redemptions and distributions. Fear Greed Tracker offers real-time sentiment analysis on over 50,000 assets, helping you gauge the market's mood and make more informed decisions. Explore our tools and data-driven insights today at https://feargreedtracker.com.